Long Range Studio Visit

Mále Uribe and Thomas O’Brien

– Not just a contemplation upon a pigment –

Mále Uribe is a Chilean architect and artist who lives and works in London. Her work explores visual perceptions of large-scale material surfaces as ‘mediums’ to alternative narratives and worlds, using the surface as a medium between physical and virtual dimensions, and between digital and crafted modes of production.

'By understanding materials as vibrant and autonomous entities that carry a transformative power, I aim to create spaces, sculptures and surfaces that promote a conscious and more imaginative relationship with our natural and built environments, where myths, chemical properties, industrial processes and microworlds merge.'

Thomas O'Brien has an explorative, critical architectural practice based in Dublin and Co. Tipperary, Ireland. It was founded in 2013 and since then has earned a reputation as an expansive practice that incorporates an ongoing examination of the complex interrelated nature of material things, humans, animals, and plants into each project.

Thomas: I'm not sure how to begin on this, the caput mortuum ultimately was for me secondary to the overall PADA experience, and as it fades a little in my memory, I find myself thinking that this conversation might be a nice way of documenting that in some way. I had not done a residency before PADA and it had a profound effect on me – I think it was a coming together of people who found easy company in each other even though there were many different strands to our work. I think the support of these new friends and the real connections made pushed me into a new more creative place for making and thinking about my work. It might sound a bit hokey, but the shared dinners and beers in the evenings were the center of this experience, beyond the art making but feeding it.

Maybe you had a similar experience?

Mále: Definitely, I treasure nostalgically the beautiful human experience that PADA was and the effect that co-living with that creative community had on me. It was a very inspiring and empathic environment – I feel like I now carry that joy with me forever. It is interesting that we were only days apart from meeting each other, and yet I feel that there was a smooth and interesting transition between our residency groups… dinner traditions, recurrent themes, conversations, films and materials that extended in time as a natural continuity of ideas and projects, ultimately nurturing our own personal work and possibilities. It is exciting to finally have a space to talk about these transitions and overlaps!

At the same time, living in a place like Barreiro is quite a unique experience; almost impossible not to get carried away by daydreaming when living surrounded by such a distinctive environment with an incredible industrial and social history. Caput mortuum became an important part of that landscape and imaginary for both of us, and it was one of those threads that extended and grew from one month to the other.

How was this material encounter for you?

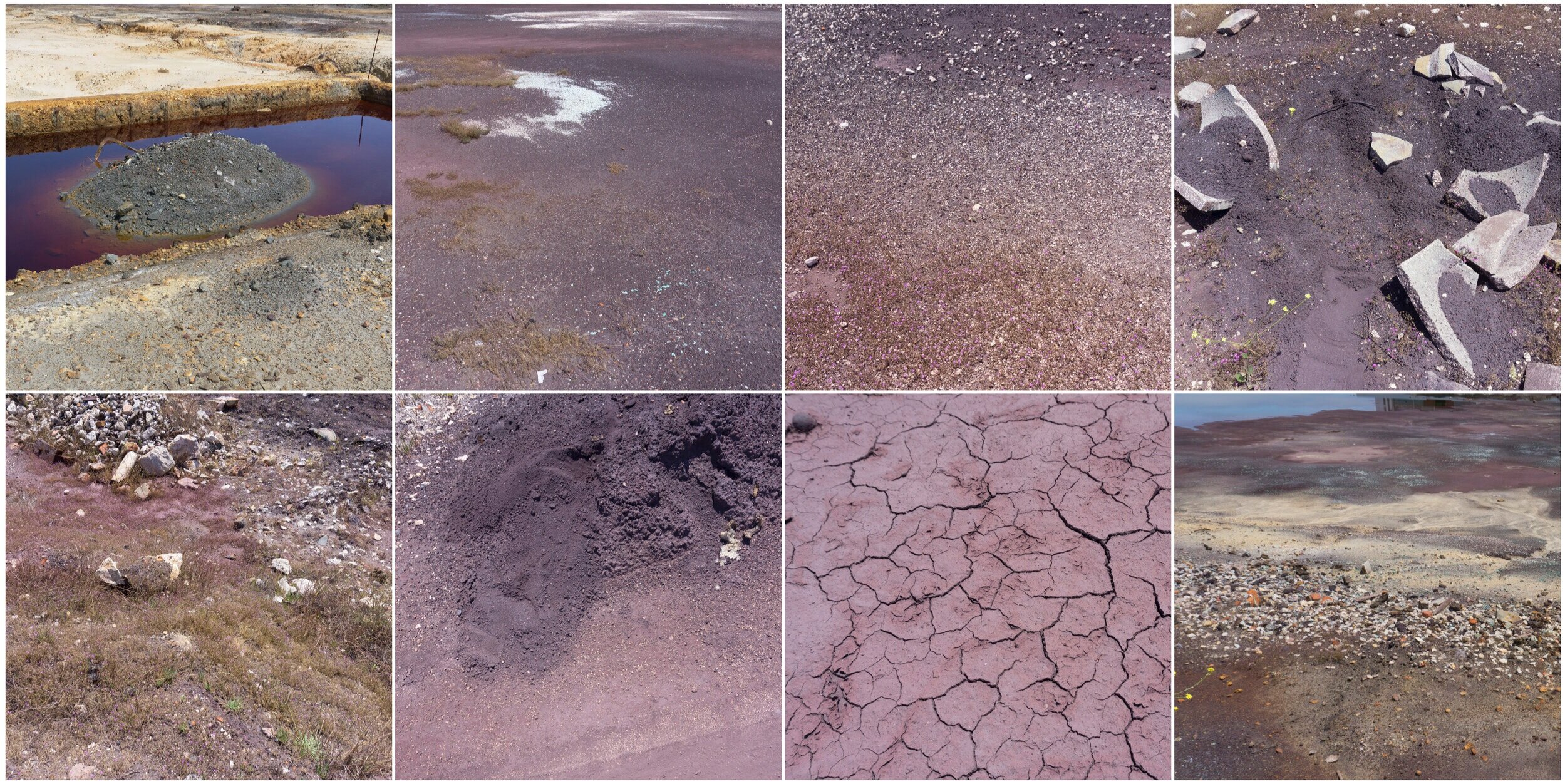

Photography by Mále, ‘PADA site research’, 2021

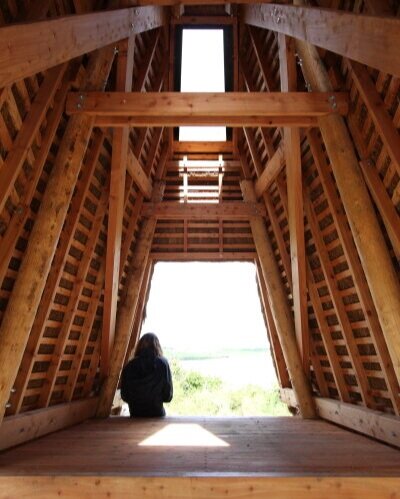

Thomas O’Brien, ‘Short Elev 2’, 2021

Thomas: Funny you should mention that imaginary landscape, this attribute of the site certainly felt very tangible. At the start of the residency I thought of making little concrete ‘band-aids’ to protect the exposed steel reinforcement of some of the concrete structures present, to make gardens out of weeds, to run up new flags on the rusted old flagpoles near the studio. I had this idea in my mind of ‘taking care of business’ – treating the wounds of the site. The presence of the founder of this place, Alfredo da Silva, laid out in his mausoleum was also on my mind – this singular man ultimately responsible for all this, who did not take care. I wanted to even take care of him in some way; to show compassion rather than anger as a tool to tackle his legacy.

To speak a little of the caput mortuum, it’s a tricky customer, and I'm still not sure about it – I didn't bring any back with me in the end as I think it is part of that landscape, it should remain there maybe as the ground that is left from the sites industrial history.

It's the ash from burning pyrite, it is now the very soil of that industrial wasteland, ashy, sulphurous, gritty, difficult to mix in oil or water., but weeds still come up through it somehow, and a few rabbits hop around so there must be life possible there if we humans just step back and let time sort it out.

It is at its most beautiful left as it is (in the ground) maybe, but there is no doubt but there's a melancholy to that beauty – it’s a pollution in the end.. and I'm not sure about melancholy in my work these days – i'm trying to get past that.. That's why I wanted to make a piece of work that sought to care for the site in some way – documenting a specific ruined building (a pyrite dump) and making a few material objects that in my mind would remain on site and perhaps form a garden, or just make themselves useful in some minor way.

Photos by Thomas, Elevation 1 & Tank, PADA Industrial Park, 2021

Thomas: In the end these concrete pieces were placed on top of an ant colony beyond the mausoleum of Alfredo de Silva. The Artist Soraya Hamlaoui and myself made a sort of garden here in this strange curved space behind the mausoleum by arranging the various artefacts we had made over the course of the residence. I can only speak for myself but I felt this was somehow conjuring a spell. It also crossed my mind the similarities between this scene and a scene from Mulholland Drive where a spell is being cast behind some very American diner by some dark Lynchian figure. It felt like something more primal than the modernist project was being juxtaposed against its back wall. I wanted to connect with Alfredo on some cosmic level. Let him know he was wrong all along.

‘Alfredo’s Garden’, Installation by Thomas O’Brien and Soraya Hamlaoui, 2021

Alfredo da Silva Mausoleum, photo by Thomas O’Brien, 2021

Mále: I saw some of the leftovers from your spell behind the mausoleum! Very intriguing scene to find! I think rituals – of any kind – can serve as important moments to close or open creative pieces. When finishing a residency or exhibition, there's always that anticlimax moment of packing things up and going home, especially when artworks are part of some form of site-specific or temporary activation. In my case, the act of returning the leftovers from the material I used back to the wasteland was an attempt to close the cycle. But to be honest I think it might be still open... maybe there are some unfinished threads to be explored.

And yes, caput mortuum is indeed quite a tricky material... Both in its chemical composition, and in the wide network of meanings that the pigment itself entails. In my work, I usually explore the lost or unheard potentials of materials that are disregarded to challenge our concept of value. So finding these colourful ashes in the wastelands of Barreiro (which looked more like a dystopian Martian paradise to me) was like finding a purple treasure... I still think about caput mortuum a lot, and in the many poetic ideas it can spark.

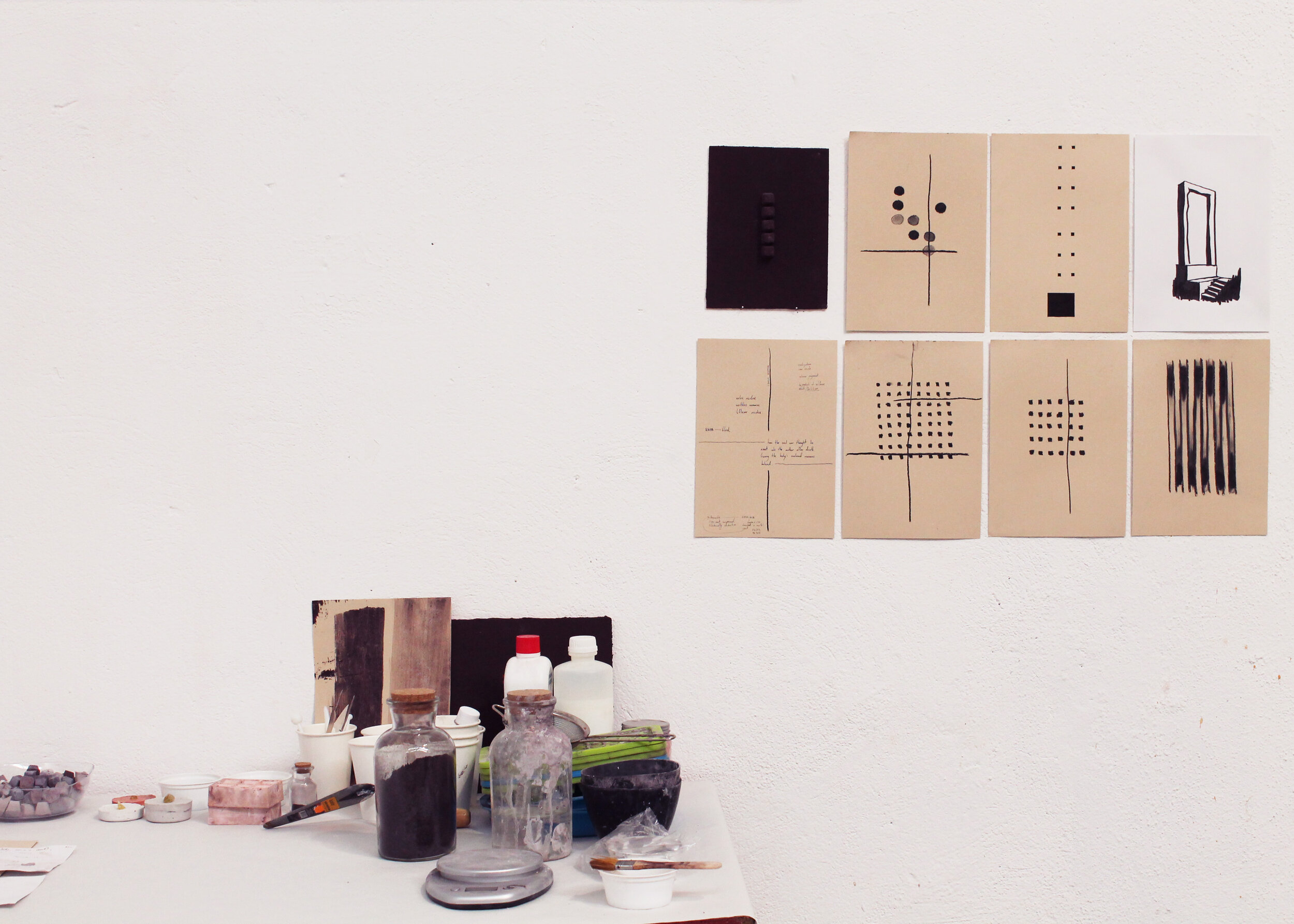

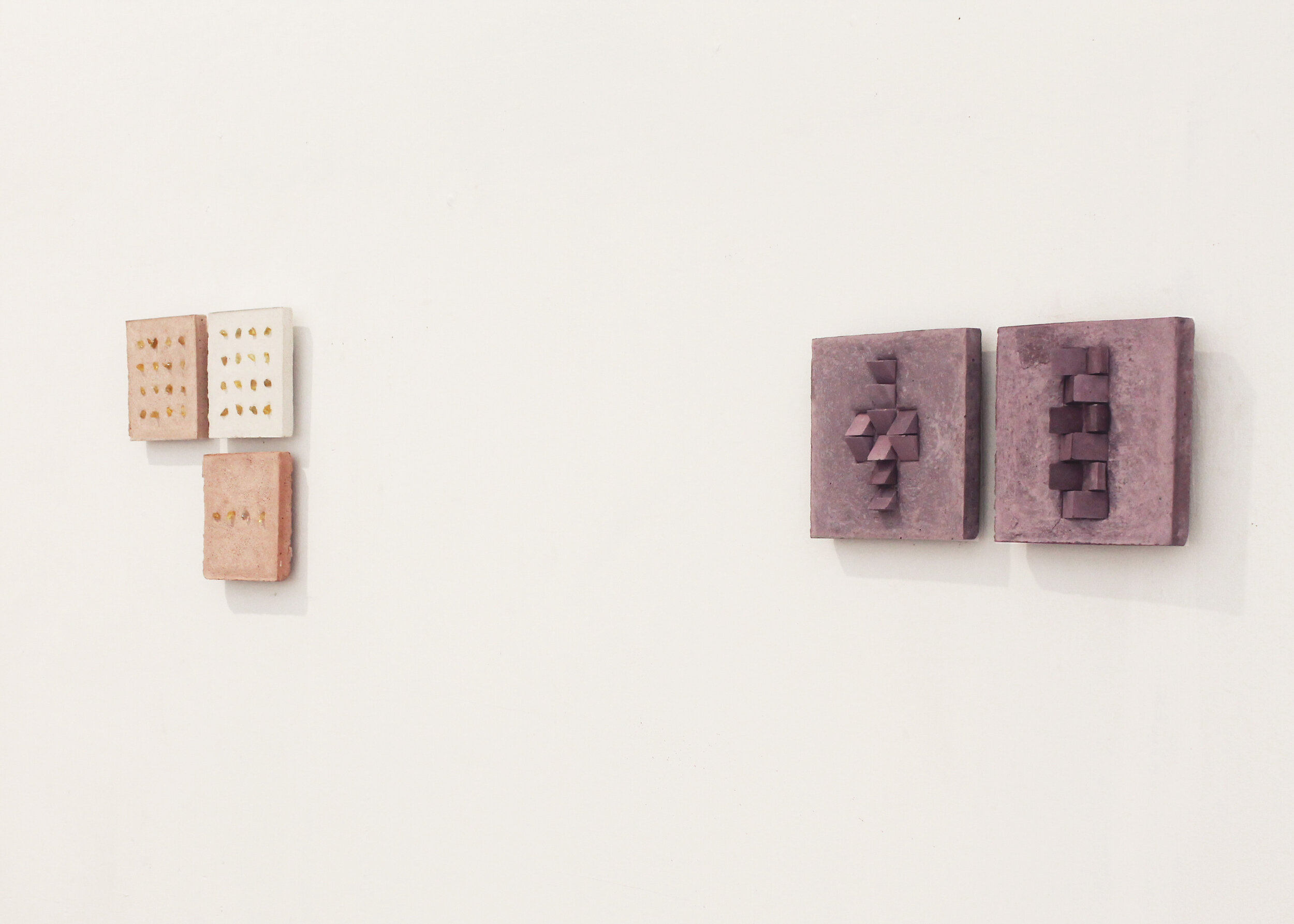

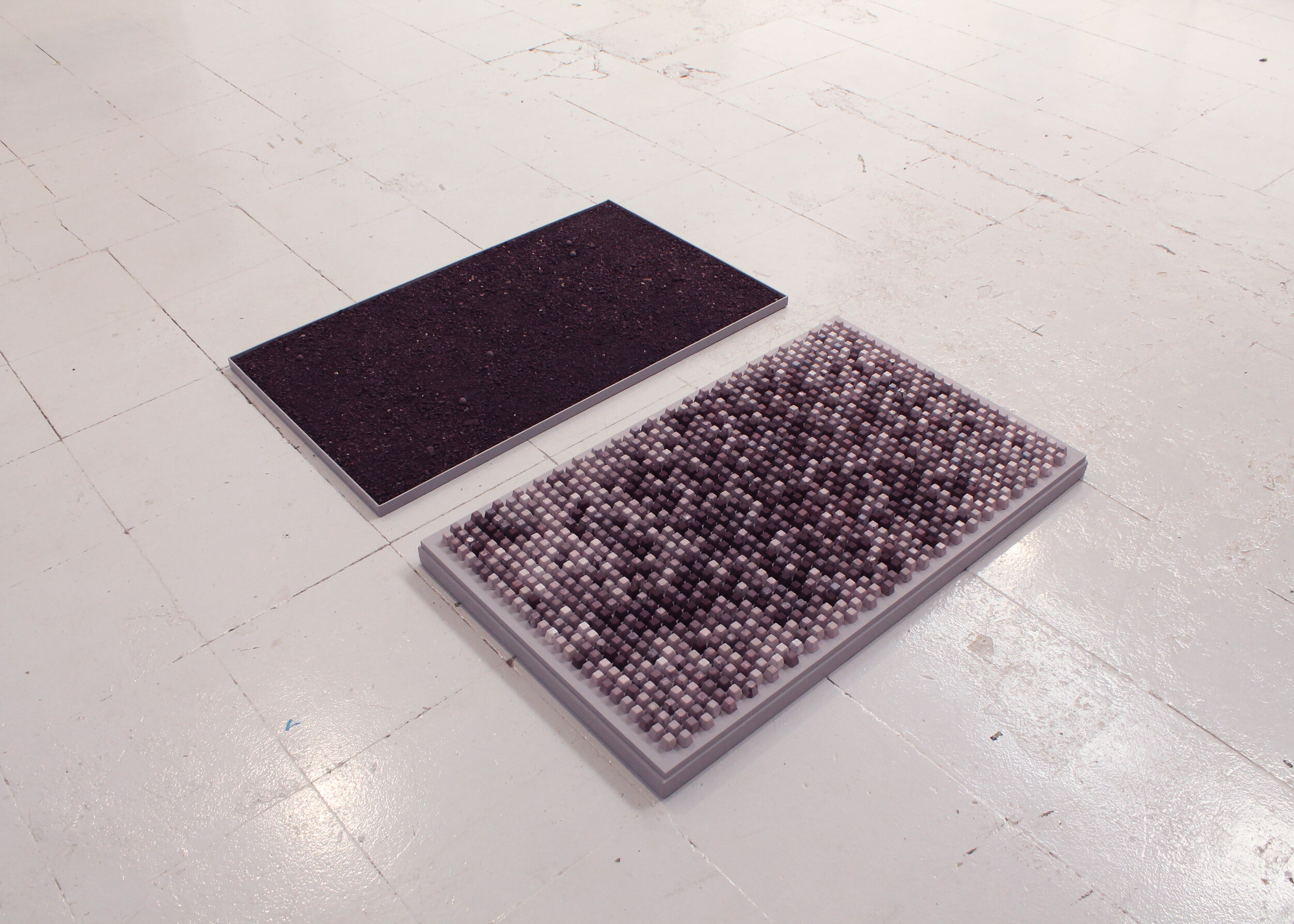

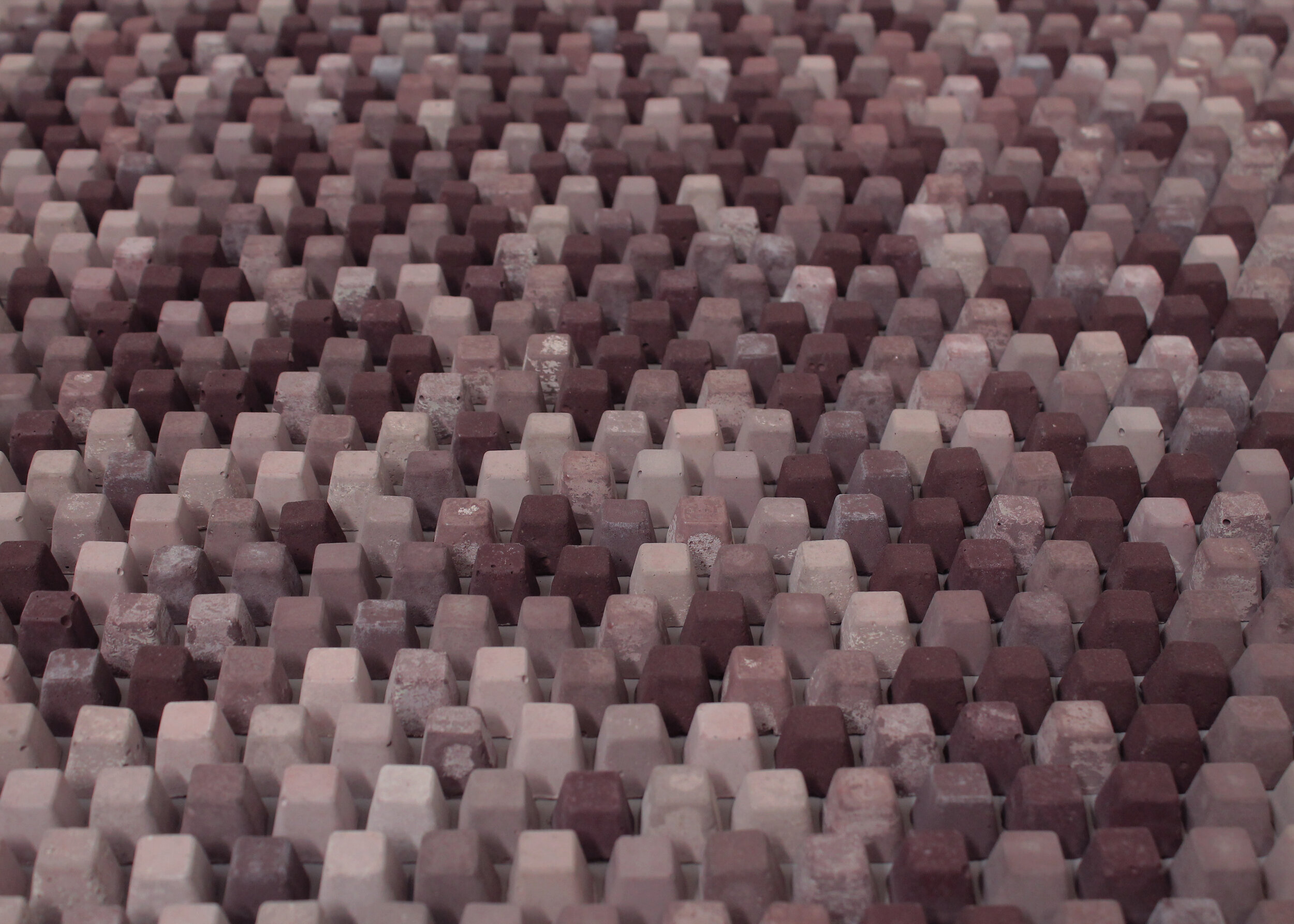

Mále: What you say about it being at its most beautiful left as is, in the ground, really resonates. The visual power of that human-created landscape is so strong that I felt the need to document it and display it, or frame it somehow as it is. My piece Residuum was the result of processing and testing the colour of these residual ashes in different mixing ratios, that I mechanically replicated into little casted pieces that composed a continuous surface. I wanted to show how materials can perform and speak in different ways depending on how we use them. But the most interesting part for me, was the process of collecting and processing the ashes to get the purest possible pigment. As part of this process, I had full buckets of my own leftovers with bigger pieces of purple gravel, that were at the same time the leftovers of a bigger industrial system from decades ago. And the term caput mortuum in itself refers to the leftovers of chemical processes… so I became obsessed with this endless loop of ‘wastes’ and decided to display my leftovers as a piece in itself before returning them to the landscape. I framed it horizontally, like a scaled model on the ground.

Mále: PADA was the perfect place to work on a site-specific research project. Working with landscapes is for me a great way to integrate some of the research tools and methods I trained in architecture within my practice in a multidisciplinary way. Your process of documenting the ruins on the site was really interesting.

How did this dialogue of disciplines work for you?

And do you think your studio practice has changed since PADA?

Thomas: I think documenting a specific part of the site – the pyrite dump, that I surveyed and photographed was ‘a way in’. It became something to focus on and coalesce ideas around.

I’m careful enough not to refer to myself as an artist but as an architect: we use architectural language. Surveying is a dumb enough tool - measure and draw what you see, but it does let you get to know the thing in more detail, aside form the measuring , it forces you to take time and look closely... I’d add to that though that in this context it was a reflection on the modernist project: that notion of empirical measure, (the architect's language) that in turn is based on a very anthropocentric idea of control, productivity and progress. So I tried to infuse the drawings with a more emotive, qualitative sensibility; a loping dog appears shuffling across the pages; alchemy symbols for the caput mortuum become a motif stamped on everything; the caput mortuum pigment gets rubbed onto the paper to color the drawings; the paper itself is a green colored graph paper found on the site, discarded from some measuring machine in a lab perhaps.

Similarly the objects I made fluctuate between a sharp precise framed aluminium structure, and the grubby tactile nature of the concrete pieces… wild thistles unceremoniously get shoved into a crack in the man made object to announce in a fairly didactic way: ‘look at us we are flowers not weeds - and we’ll be here longer than you in the end’ .. There’s a bit of humor in that move too - in Ireland we have a saying: ‘he might as well be looking into a field of thistles’.. That's me most of the time.

Thank you to Mále Uribe and Thomas O’Brien for discussing about their experience at PADA.

Thomas O’Brien was a PADA Resident in April 2021 and Mále Uribe in May 2021.